19 Dec The link between cancer and nutrition

Cancer is the single biggest cause of death in Aotearoa New Zealand. But by 2040 the number of Kiwis diagnosed with cancer is predicted to double(1).

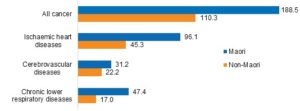

The burden of cancer is felt more greatly by Māori, Pacific people and low socio-economic groups. Māori are 30% more likely to get cancer and have a mortality rate 1.7 times greater than non-Māori (2)(3) (see Table 1). The most common cancers in Aotearoa New Zealand are: lung, colorectal, skin cancers including melanoma, breast and prostate cancers. As many as fifty percent of cancers are potentially preventable, so there are many opportunities existing to reduce cancer’s incidence and impact (4)(5).

Table 1: Māori and non-Māori mortality rates for leading causes of death, 2016

Note: rates per 100,000 population, age-standardised to WHO World Standard Population.

Source: Mortality 2016: Data tables, Mortality Collection, 2019 (3)

Smoking, alcohol, physical activity, eating patterns and weight throughout life are major influences on cancer risk (4)(6). Nutrition and weight are the biggest cause of cancer after smoking. The Third Expert Report, Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Cancer: a Global Perspective (2018) brings together a growing body of evidence on preventing and surviving cancer through diet and physical activity from the Continuous Update Project (CUP)(4).

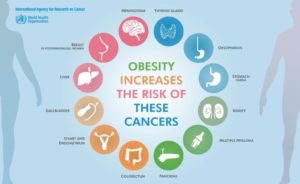

Weight and cancer risk

The Continuous Update Project finds strong evidence for causal links of high body fatness with 12 of 17 cancers. These include oesophagus, pancreatic, colorectal, post-menopausal breast cancer, liver, endometrium, kidney, mouth, pharynx, larynx, stomach, gall bladder, ovarian and advanced prostate cancer (4)(6). Greater weight gain as an adult increases the risk of post-menopausal cancer and cancer-related mortality in breast cancer survivors (4). In general, the more excess weight an adult has, the higher the risk of some cancers. The exception is for premenopausal breast cancer where the risk is generally lower. Up to a third of these cancers may be due to an unhealthy diet and being overweight (7). In 2012, approximately 6% of all cancer cases could have been avoided if no New Zealander had any excess body weight (8).

Inflammatory, endocrine (such as growth and sex hormones), and metabolic abnormalities such as raised oestradiol and insulin associated with obesity, underlie cell growth and cancer risk (6). The good news is that sustained, planned weight loss can reduce cancer risk. Evidence is especially convincing for those with breast and endometrial cancer (6). Achieving and keeping to a healthy body weight provides cancer protection (4). Interestingly, although not easily modifiable, developmental factors such as higher adulthood height and heavier birthweight, are also linked to greater risk of some cancers.

Table 2: Obesity-Related Cancers

Eating patterns and cancer risk

Eating patterns can also impact cancer risk (4). Strong evidence supports probable protection of wholegrains, fibre and non-starchy vegetables for colorectal and other cancers. This is likely related to their rich source of micronutrients such as vitamins C, E, selenium, folate and phytochemicals.

Dairy products also convey probable protection for colorectal cancer as do calcium supplements. Breastfeeding also protects against breast cancer.

Limited evidence links fruit with protection against some cancers and low intake with stomach and colorectal cancers. Sugar-sweetened beverages, while not directly impacting cancer risk, do increase the risk of weight gain and obesity and subsequently cancer risk.

Limited evidence links fruit with protection against some cancers and low intake with stomach and colorectal cancers. Sugar-sweetened beverages, while not directly impacting cancer risk, do increase the risk of weight gain and obesity and subsequently cancer risk.

Alternately, strong evidence supports a convincing causal relationship between processed meat (salted, smoked or fermented such as ham, salami, bacon, pastrami and some sausages) with colorectal cancer risk. Consumption of red meat has a probable causal link with colorectal cancer. The more consumed the greater the risk. Possible mechanisms include the high temperatures used in cooking meats, such as grilling or barbecuing. This results in heterocyclic amines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons which have been linked to colorectal cancer in experimental studies. Additionally, the haem iron in red meat or the nitrites in processed meats, used for colours and flavours, may stimulate cancer through the formation of N-nitroso compounds such as nitrosamine. Salt used in processed meats or processing may enhance cancer risk through mucosal changes, N-nitroso formation, stimulation of Helicobacter Pylori and cellular damage.

Strong evidence also links glycaemic load with endometrial cancer and high dose B carotene supplements with lung cancer.

Recommendations for individuals

Overall, to protect against cancer the World Cancer Research Fund (2018) makes ten recommendations. They promote a plant-based diet rich in fruit, vegetables, wholegrains and legumes, throughout life and discourage a reliance on supplements (7). Their recommendations are:

- Be a healthy weight.

- Be physically active.

- Eat a diet rich in wholegrains, vegetables, fruit and lentils and legumes.

- Limit ‘fast foods’ and other processed foods such as fat, starches or sugars.

- Limit sugar sweetened drinks.

- Limit red and processed meat.

– If you eat red meat, limit consumption to no more than about three portions (350–500g cooked weight) per week.

– Eat very little or avoid processed meat such as bacon, ham, sausages, salami.

- Limit alcohol.

- Do not use supplements for cancer prevention.

- Breastfeed if you can.

- After cancer diagnosis follow these recommendations if you can.

Population prevention strategies

Being overweight or obese are not problems of individuals but of society and are the result of environmental wide issues (9)(10). Prevention strategies to effectively impact obesity are complex. A comprehensive population approach is needed rather than focusing on the individual (11). Food environments in Aotearoa New Zealand are largely unhealthy (12). Regulation and community campaigns are needed to impact the external drivers of lifelong nutrition inequalities (13)(14)(15). The World Cancer Research Fund public health and policy recommendations based on the NOURISHING framework endorse influencing food environments, food systems and food behaviours through (16) the following strategies.

- More information on labelling and packaging.

- Food standards in school, workplaces and health facilities.

- Health levies on sugary drinks and subsidies on healthy food.

- Government-led standards for food marketing especially to children.

- Government-led targets to reduce sugar, salt and fats added to our food.

- Community regulations and incentives to increase the availability of healthier food especially in more vulnerable communities.

- Healthy urban design to restrict food outlets and incentives for healthier retail outlets to be located in underserved areas.

- System changes to public procurement and food production.

- Raising public awareness and communication about healthy food practises.

- Nutrition counselling and skills development.

The Cancer Society of New Zealand is currently planning its health promotion focus for the next few years. This is likely to include addressing stronger public awareness of the obesity and cancer links and advocacy for policies to restrict both marketing to children and a sugary drinks tax.

This article was written by Vicki Robinson, Health Promotion Advisor, Cancer Society NZ

Bibliography

- Ministry of Health. Mortality 2016: Data Tables (provisional) Ministry of Health. [Internet]. 2018. Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/nz-health-statistics/health-statistics-and-data-sets/cancer-data-and-stats

- Ministry of Health. New Cancer Registrations 2016 [Internet]. Wellington NZ; 2018. Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/new-cancer-registrations-2016

- Ministry of Health. Mortality 2016 Data Tables [Internet]. Wellington; 2019. Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/mortality-2016-data-tables

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Cancer: a Global Perspective [Internet]. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018. 2018. Available from: https://www.wcrf.org/dietandcancer

- World Health Organisation. Cancer, Cancer Prevention [Internet]. Available from: https://www.who.int/cancer/prevention/en/

- World Health Organisation. Absence of XS Body Fatness: Volume 16 [Internet]. International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2018 [cited 2019 Nov 25]. Available from: file:///C:/Users/vicki/Downloads/HB16-BOOK-0606 (3).pdf

- Whiteman DC, Wilson LF. The fractions of cancer attributable to modifiable factors: A global view. Cancer Epidemiol. 2016;44(203–221).

- Arnold M, Pandeya N, Byrnes G, Renehan AG, Stevens, G. A., Ezzati, M., Forman D. Global burden of cancer attributable to high body-mass index in 2012: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol [Internet]. 2015;16(1):36–46. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanonc/article/PIIS1470-2045(14)71123-4/fulltext

- Kumanyika SK, Parker L, Sim LJ. Bridging the evidence gap in obesity prevention: A framework to inform decision making. Bridging the Evidence Gap in Obesity Prevention: A Framework to Inform Decision Making. 2010.

- Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Heal Organ – Tech Rep Ser. 2000;

- Prof Nick Wilson, Cleghorn DC, Cobiac DL, Mizdrak DA, Prof Cliona Ni Mhurchu PTB. Dietary counselling – how effective and cost-effective is it? [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 16]. Available from: https://blogs.otago.ac.nz/pubhealthexpert/2018/03/19/dietary-counselling-how-effective-and-cost-effective-is-it/#more-3030

- Vandevijvere S, Mackay S, D’Souva E, Swinburn B. How healthy are NZ food environments? 2014-2017 [Internet]. 2018. Available from: file:///C:/Users/vicki/Downloads/INFORMAS Food Environments 201B Full Report.pdf

- World Health Organization. Report of the Commission of Ending Childood Obesity. WHO. 2016;

- World Health Organization. “Best buys” and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. WHO. 2017;

- Health Coalition Aoteoroa. Unhealthy Food [Internet]. Available from: https://www.healthcoalition.org.nz/health-issues/unhealthy-food/

- World Cancer Research Fund International. Recommendations and public health and policy implications [Internet]. 2018. Available from: https://www.who.int/end-childhood-obesity/publications/echo-report/en/